Subways Seeded the NYC Epidemic: MIT Economist

Like so many of us, Bret Stephens, an opinion columnist for The New York Times is stunned at the concentration of COVID-19 virus deaths in New York City, as well as the rest of the metropolitan area. In an April 25, 2019 article entitled “America Should Not Have to Play by New York Rules,” Stephens points out that the “number of Covid deaths per 100,000 residents in New York City (132) is more than 16 times what is in America’s next largest city, Los Angeles (8).”

Stephens says, “it isn’t hard to guess why,” going on to note “Commuters crowd trains, office workers crowd elevators, diners crowd restaurants. No other American city has the same kind of jammed pedestrian life as New York — Times Square alone gets 40 million visitors a year — or as many residents packed into high-rises.” This is the issue of “exposure density,” that we raised a couple of weeks ago.

New York City’s Hyper-Densities

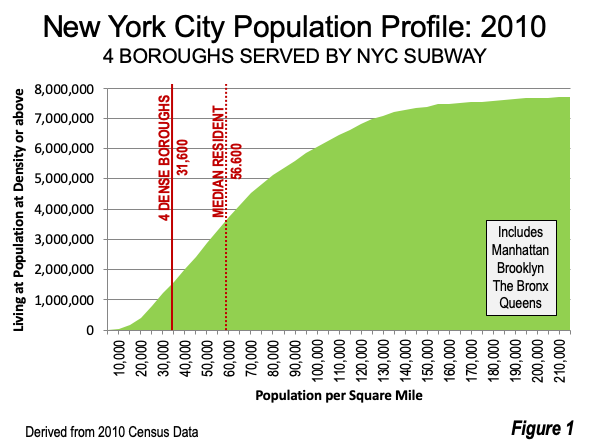

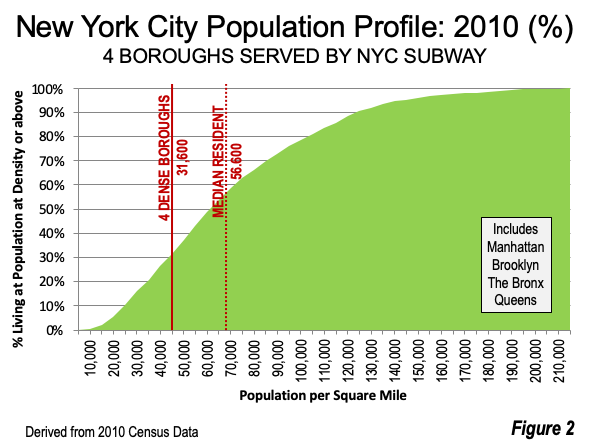

Stephens appropriately mentions overall population density. But overall measures of city population density significantly underestimate the risk. The vast majority of New Yorkers in live at population densities far higher than the New York City average. The population density of the four boroughs served by the New York City Subway (Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx) is about 31,600 per square mile (12,200 per square kilometer), yet 78% of the population lives at much higher densities than these averages. The median resident — half live at higher densities and half live at lower — lives at a density of 56,600 per square mile (Figures 1 & 2). City-wide densities do not begin to quantify the exposure risk of neighborhood and employment densities.

The MIT Research

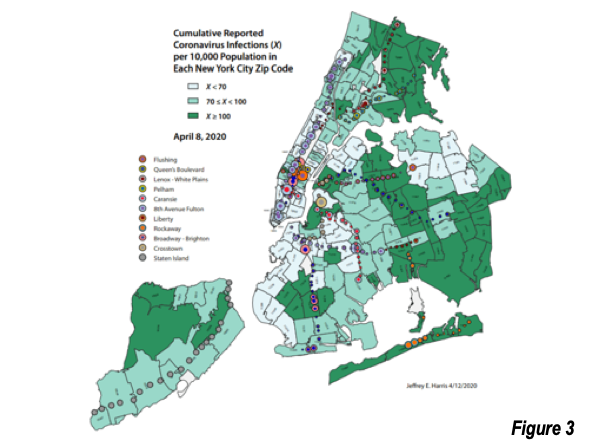

Particular attention has been brought to the subways by long time Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) economics Professor Jeffrey E. Harris. Harris, who also has a medical degree, specializes in health economics and has a publishing record dating back decades, finds that “The parallel between the continued high ridership on MTA subways and the rapid, exponential surge in infections during the first two weeks of March at best supports the hypothesis that the subways played a role.” His more than adequately caveated working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research — “The Subways Seeded the Massive Coronavirus Epidemic in New York City, describes the association between subway ridership and New York City’s high infection rate.

Harris uses the example of commuter he calls “Milagros,” riding the Flushing Local line (Line 7), which runs from Hudson Yards in Manhattan to the Flushing Main Street Station.

Milagros’s exposure to coronavirus is not accurately gauged by the number of commuters who passed through the turnstile at her entry point at Junction Boulevard. That is because she will come into contact with potentially infectious passengers at each of the remaining 17 stops until she gets off at 34th Street–11th Avenue, which happens to be located in another coronavirus hotspot.

Harris further suggests four factors that increase the rate of infection on the subways.

- Infection increases with the “number of trips and average number of stations per trip along the entire subway line, and not just to the number of entries at any one subway station.”

- “Second, passengers entering the subway line even at a remote, less populous station are slowing down the system” thus increasing the travel time. This increases exposure risk.

- “Third, those uninfected S-passengers (susceptible passengers-ed) who cram shoulder-to-shoulder into a particular subway are increasing train-car density and thus raising the average number of other S-passengers infected by an I-passenger (infected passenger-ed) who happens to be standing in the middle of the train.”

- “Fourth, local trains – like the Flushing local – are more likely to seed epidemic infections than express lines.” (I might add, there are lot more riders on local trains than express trains, which operate less frequently and not on all lines, and I suspect carry a much less affluent ridership)

He concludes that “an entire subway line, rather than the individual stations or subway cars, is the appropriate unit of analysis. (Figure 3)”

All of this has reaped substantial pushback, which is to be expected since New Yorkers generally like their city (as I do). One pundit went so far as to say that people should “absolutely not” avoid public transportation in New York, as if to suggest that social distancing is unnecessary.

However, even New York’s Mayor Bill DeBlasio is distancing himself from that kind of cheerleading, commenting that “Early on we said to people, if you don’t need to go on the subway, don’t; if you can work from home, work from home; if you can walk or bike or anything else, do so.”

Either the COVID-19 virus spreads in a manner that requires social distancing, or it does not. It is an Orwellian fantasy to think that social distancing can be maintained on a subway train.

New York’s Governor Weighs In

Inconveniently for this point of view, according to the New York Post:

Gov. Andrew Cuomo provided frightening new details about the durability of the coronavirus — telling New Yorkers that the virus can linger in the air for up to three hours and survive for three days on plastic and steel surfaces commonly found on trains and buses.

Referring to the virus, Governor Cuomo said: “It can live on a pole in a bus or on a seat in a bus for up to 72 hours.”

There is More to the Story

At the same time, Harris points out that the subways are not the only cause: “We know that it would be inappropriate to require the subway hypothesis to explain every aspect of the diffusion of coronavirus.”

Obviously, the addition of the other factors makes things much worse. It is challenging to socially distance in New York City, with the interplay between population density, employment density, crowded commuting and crowded elevators, and just much more human interaction that intensify exposure densities. Social distancing is far easier in urban environments without the intense exposure density of New York City.

Responding with Understanding

It should go without saying that evaluation of the COVID-19 spread needs to be objective. This means that it needs to include all potentially factors, even the most “politically correct”, such as density — especially the exposure density from how we live, work and get around.

The subways are an important part of this in New York City. As Harris notes, “We know that close contact in subways is fully consistent with the spread of coronavirus, either by inhalable droplets or residual fomites left on railings, pivoted grab handles, and those smooth, metallic, vertical poles that everyone shares.”

Meanwhile, the signs are ominous. Already, Capital Economics has suggested that we are entering the worst global recession since World War II and that the economy “will take years to return to its pre-virus path. ”Obviously, the human misery will be great, from job losses to home losses, greater poverty, personal anguish and increased rates of suicide. We need understand what happened and why.

Photograph: Long Island, Queens, with mid-town Manhattan and Central Park across the Ed Koch Queensboro (59th Street) Bridge and New Jersey beyond, across the Hudson River (by author). New York City’s Flushing Subway Line operates through Long Island City, tunneling under the East River, just south (to the left) of the bridge on the way to Grand Central Station and Hudson Yards.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed by Mayor Tom Bradley to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. Speaker of the House of Representatives appointed him to the Amtrak Reform Council. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Mike Scheid

Mike Scheid