Economics Needed for People-Based Urban Planning: Alain Bertaud Book Review

Alain Bertaud’s new book, Order without Design: How Markets Shape Cities (MIT Press), is particularly timely, because of the rising concern about the challenges facing middle-income households. The broad based affluence that followed World War II brought unprecedented affluence to many millions of people, principally in the high income nations. This also raised the standard of living for people living in or near poverty. The progress has been well documented by economists, such as Diedre McClosky and Robert Gordon.

Alain Bertaud’s new book, Order without Design: How Markets Shape Cities (MIT Press), is particularly timely, because of the rising concern about the challenges facing middle-income households. The broad based affluence that followed World War II brought unprecedented affluence to many millions of people, principally in the high income nations. This also raised the standard of living for people living in or near poverty. The progress has been well documented by economists, such as Diedre McClosky and Robert Gordon.

Bertaud has had a long career in urban affairs and was principal urban planner for the World Bank. He has consulted for governments around the world and earned an Architecte DPLG diploma from the prestigious Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Bertaud is currently a senior research scholar at the NYU Marron Institute of Urban Management, a program led by Nobel Laureate Paul Romer (Economics). Early in his career he was assigned to Le Corbuseier’s fabled Chandigarh, a planned city some consider perfect architecturally, that serves as two Indian state capitals, and is a World Heritage site.

The Middle-Income Decline

Over the last century, the prosperity expanded broadly in middle-income nations. Yet, there is considerable evidence that this trend is reversing, as documented by French economist Thomas Piketty. His research shows that the substantial increase in international wealth equality that occurred in the post war decades has ended. One key factor has been the huge housing cost increases that have driven hundreds of thousands of middle-income households away from high cost locales, such as California, and metropolitan Toronto. It is also evident across Australia, the United Kingdom and New Zealand, where pervasive hyper-inflation of house and residential land costs have severely reduced the discretionary incomes that are the very basis of middle-income lifestyles.

Bertaud is expert in much, including how wealth is created and distributed.

Cities: Incubators of Affluence

Bertaud is an urbanist of the highest order, reminding us that “cities are the major engines of economic growth, and living in cities is the only hope of escaping poverty for billions of people.” This is because cities are labor markets, a fundamental principle of urban economics.

He contends that current planning practices place “constraints put on the supply of urban land and floor space by restrictive regulations” that “are causing severe urban dysfunctions.”

According to Bertaud, urban planners pay insufficient heed to urban economics:

I think that, worldwide, the unfamiliarity with basic urban economic concepts by those in charge of managing cities is one of the major problems of our time.

He continues:

…the professionals in charge of modifying market outcomes through regulations (planners) know very little about markets, and the professionals who understand markets (urban economists) are seldom involved in the design of regulations aimed at restraining these markets.

He concludes that:

Unfortunately, to this day the knowledge accumulated in this economic literature seldom percolates into urban operational planning practices, and urban regulations detrimental to the welfare of citizens still survive unchallenged.

Restrictive Regulations

Bertaud sees the restrictive land use planning regulations that have proliferated around the world as a major problem. He has particular criticism for urban containment policy, which outlaws or significantly restricts new housing on the urban fringe. He cites the extensive economic evidence associating urban containment with higher house prices.

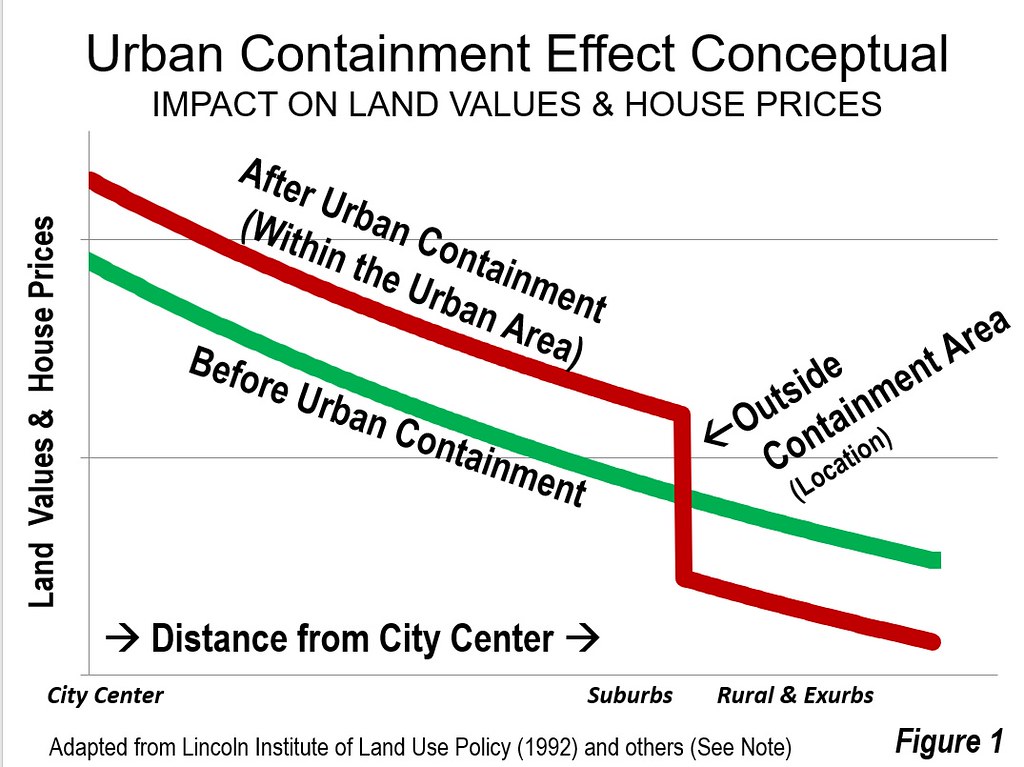

I have often used variations of Figure 1, below, to illustrate how urban containment raises land and thus house prices. Our research shows that housing cost differences account for 75 percent to 85 percent of the cost of living difference between more expensive US metropolitan areas and the average. Consistent with this, economist Matthew Rognlie found that nearly all the rising inequality in wealth was to be found in the housing sector. Bertaud notes that restrictive regulations have expanded over time, “with virtually no cost-benefit analysis.”

Bertaud suggests that such regulations conflict with urban economics, adding that:

Poorly conceived urban strategies are not just innocent utopias. They misdirect scarce urban investments toward locations where they are the least needed and, in doing so, greatly reduce the welfare of urban households. These failed strategies make housing less affordable and increase the time spent commuting.

So What are Planners to Do?

Bertaud is making the case that, for people, cities must be affordable and as labor markets, there must be mobility options that maximize job access. His prescription for what planners should do is very simple.

The main objective of the planner should be to maintain mobility and housing affordability as a city’s population increases and it diversifies its activities (emphasis added).

Obviously, preserving and enlarging the middle class and reducing poverty requires focusing on these objectives. Yet, more often than not, modern urban planning imposes the opposite — land use regulations strongly associated with higher house prices, which translates nearly directly into a higher cost of living and lower standard of living. Moreover, a higher cost of living means more poverty, as is demonstrated by California’s highest poverty rate among the 50 US states (adjusted for housing costs).

Bertaud notes that “The objective of an urban transport strategy should be to minimize the time required to reach the largest possible number of people, jobs, and amenities.” Fortunately, significant strides have been made in recent years to estimate the number of jobs that can be reached by the average residents in US metropolitan area by different transport modes. Yet, I have seen no evidence that this crucial indicator is being given sufficient priority among planners. There can be nothing so fundamental in planning transport in a labor market than access to work.

There is Much More

This is just a quick overview of a book packed with analysis and prescriptions integral to improving the lives of people, by making cities better meet their needs. He also dismisses the “jobs-housing balance,” which ….”does not exist in the real world, because it contradicts the economic justification of large cities: the efficiency of large labor markets,” and “exists only in the minds of urban planners.” He notes that misplaced emphasis on the design of cities — “to coerce a city’s shape into an arbitrary predetermined form or an arbitrarily set density” — leads to adverse consequences.

The Prerequisite: “Departments of City Planning and Economics”

Current planning is pointed in the wrong direction for any interested in preserving the large number of middle-income households, raising households out of poverty and improving income inequality measures.

In the longer run, the solution lies in strategies that maintain or improve mobility and housing affordability, which leads to a better standard of living. This will require urban policies that rely upon rather than neglect urban economics. As Bertaud puts it:

…I suggest calling the city planning department “City Planning and Economics”

Note: Chart concept based on Gerrit Knaap and Arthur C. Nelson, The Regulated Landscape: Lessons on State Land Use Planning from Oregon, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 1992; William A. Fischel, Zoning Rules! The Economics of Land-use Regulation, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2015; Gerard Mildner, “Public Policy & Portland’s Real Estate Market,” Quarterly and Urban Development Journal, 4th Quarterly 2009: 1-16, and others.