Communities Benefit from the Expansion of Prison Education Programs

Government spending went through the roof amidst COVID-19 with approximately $4.5 trillion being spent on aid and relief for victims of the pandemic.[1] As the economy retracts, policymakers find it more necessary to implement a fiscal policy that limits continuous excessive government spending.

One area of fiscal concern has been the cost of housing prison inmates, which is estimated at $81 billion according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice.[2] The estimation increases when the indirect cost of maintaining prisons and the decreased rates of employment and education is calculated.

Incarceration is not uncommon to the everyday American. After a robust growth in U.S. incarceration starting in the 1980s, more than six in every 1,000 people in the population are behind bars.[3] The U.S. has become the nation with the highest incarceration rate in the world, contradicting the once touted title as the “Freest country in the world”. Policy makers should act urgently to craft legislation that would mitigate these rates and reduce the cost of imprisonment.

They should begin by considering the expansion of prison education due to its proven ability to curb incarceration rates by decreasing the likelihood of recidivism. In fact, several studies prove that investing in and expanding prison education positively impacts employment and wages of released inmates, which benefits the economy and society at large.

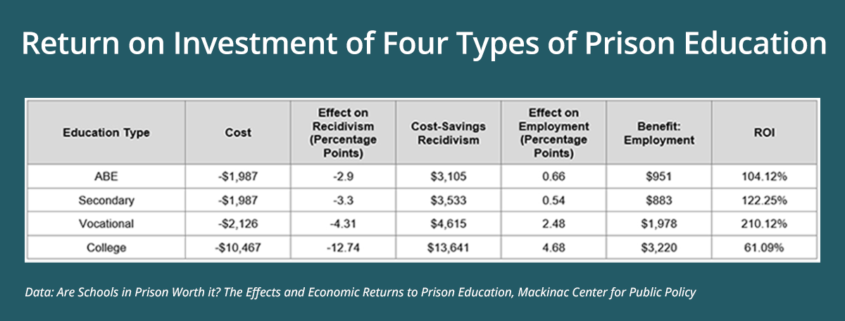

A meta-analysis titled “Are Schools in Prison Worth It?” conducted by Steven Sprick Schuster and Ben Stickle at the Middle Tennessee State University Political Economic Research Institute measured the effects of different forms of prison education on recidivism, post-release employment, and post-release wages. Unlike previous studies that portrayed the inefficiency of prison education programs, their thoroughly conducted study found significant results that suggest that all forms of prison education (Adult Basic Education, Secondary, vocational, and college) reduce recidivism and increase post-release employment and wages.[4]

By combining data from each study, they estimated the average cost of imprisonment to be $40,028 per prison year, and the Bureau of Justice Statistics[5], which estimated the average prison stay to be 2.7 years, found that each return to prison costs approximately $107,000 per inmate. Thus, each program, which reduces recidivism, has promising returns on investments. Because college education was the most expensive, it had the lowest return for each dollar spent on the program- $1.61. Vocational education yields nearly twice as much as a college education at $3.10. ABE and Secondary education yield $2.05 and $2.25, respectively. Essentially, even the smallest return would justify the cost of prison education.

Prison rehabilitation in the U.S. has been met with skepticism throughout history, stemming from the mid-1970s “nothing works” mindset that influenced bi-partisan support for increasingly punitive prison sentences and reduction in education programs.[6] As a family member of formerly incarcerated people, I was tremendously impacted by prison programs that allowed my loved ones to grow and become more career oriented.

My grandfather was imprisoned and sentenced for 15 years when I was five years old. My main form of communication with him was through letters. I would check the mail almost daily, hoping that I would receive a letter from the Federal Correctional Institution in Milan, MI. His letters always included a funny story and illustrations to go with them. It ignited a sense of narration and storytelling that I carry with me today. Teachers were surprised that my reading and writing skills surpassed the kindergarten level and were desperate to know the secret from my parents.

Today, I realized that education truly is in the hands of the beholder. My grandfather only made it to 3rd grade and barely spoke English. Still, he found himself fascinated with English literature in prison as a part of the education programs offered to him. Interestingly, The Grapes of Wrath captured his attention and remained his favorite.

Programs such as these transcend the descendants of inmates, who also become at risk of future incarceration. It sends a message of hope and potential while also accomplishing significant economic returns on investment. Policymakers should not hesitate to implement legislation that would expand these programs for the greater good of a safe and economically stable society.

To read the study summary visit the Mackinac Center for Public Policy at: https://www.mackinac.org/s2023-01

[1] https://www.usaspending.gov/disaster/covid-19?publicLaw=all

[2] https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/money.html

[3] https://www.prisonstudies.org/highest-to-lowest/prison_population_rate?field_region_taxonomy

[4] Schuster, Ben & Sprick, Steven. 2022. “Are Schools in Prison Worth it? The Effects and Economic Returns to Prison Education” Mackinac Center for Public Policy

[5] https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/time-served-state-prison-2018

[6] Martinson, Robert. 1974. “What works? Questions and answers about prison reform.” The Public Interest 35:22-54

Cruz Garcia is a research fellow at the Urban Reform Institute. He received his masters degree from the Pepperdine School of Public Policy and his undergraduate degree from the University of Michigan College of Literature Sciences and Arts. His past research has focused on domestic politics and economic mobility in low-income communities.