Ultimate Agglomeration Diseconomy: The Standard of Living

Important new ground was broken by Judge Clark, Senior Director of and Research at the Cicero Institute in his Breakthrough Institute Journal essay. In “Sprawl is Good: The Environmental Case for Suburbia,“ he topples foundational assumptions underlying the planning battle against urban expansion (the ideological term is “urban sprawl”).

Issuing a challenge, Glock talks of the “Long Triumph of Sprawl,” describing a “clear global and long-term preference,” while the “pandemic has only made the shift toward the modern, sprawling city more rapid and obvious.”

Glock suggest that “instead of warring against sprawling cars, planners and environmentalist should recognize how the green spaces of suburbia allied to autonomous electric vehicles in green single-family houses can provide both the affordability and sustainability most Americans crave.“

Glock starts with “agglomeration effects,” often cited to justify higher densities and to discourage suburbanization.

Noting that there can be negative agglomeration effects, Glock offers congestion, crime, and pollution as examples. He says that: “that these problems explain why, as technology has evolved, people try to get more of the benefits of living near each other — the agglomeration effects — without the problems of living directly on top of one another.” This has been the historic driver of urban expansion.

Glock notes that “sprawling and car-dependent cities have grown more rapidly than dense ones for decades and are far more affordable.” The former is explained by the latter. People are moving to sprawling, car-dependent cities because they are affordable.

In a strong rebuke of the most obvious densification, Glock shows that taller buildings are more expensive: “Going from five to ten stories increases the cost of each square foot by over 50 percent.” He explains, “Those costs are the result of more—and more energy-hungry—material,” a point often emphasized by Tony Recsei, President of Save our Suburbs in Sydney.

But there’s more. Glock cites the inherent climate benefits of California, which are muted since its prohibitive cost of living has repelled 2.7 million net domestic migrants since 2020, as many people as live in the city of Chicago. Glock points out that:

“Every home not built, no matter where it is located, is keeping at least two more people out of California, which is effectively doubling those persons’ carbon emissions. It is difficult to imagine many laws with such a deleterious climate impact, made worse because it exacerbates what attorney Jennifer Hernandez has called California’s “Green Jim Crow.”

In many metros, agglomeration economies have been swamped by diseconomies that have reverberated to the detriment of people, especially the middle class, and worse, those with lower incomes.

Ultimate Agglomeration Diseconomy: A Lower Standard of Living

On balance, agglomeration effects should be positive, and people should be beneficiaries.

In Under Pressure: The Squeezed Middle-Class the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reported that the future of the middle-class is threatened by costs of living that are rising far faster than incomes. Moreover, OECD indicated that “Housing has been the main driver of rising middle-class expenditure,” and that the largest housing cost increases are in the costs of ownership rather than rents.

This was not always so. As late as 1970, there was slight variation in housing affordability between major US metropolitan areas. Virtually all major metropolitan areas of the United States were affordable — with median multiples (price-to-income ratios) of 3.0 or less. Australia, Canada and New Zealand retained similar affordability until the early 1990s.

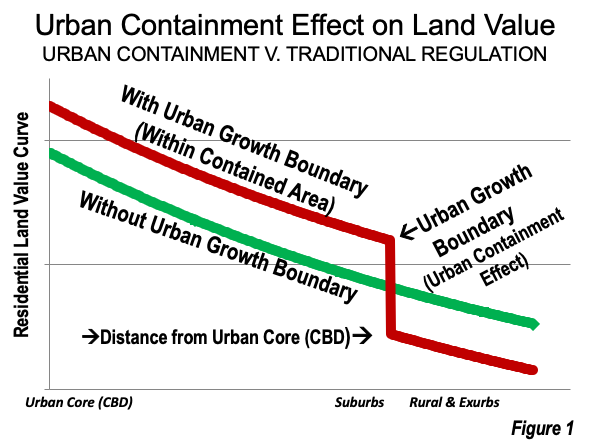

This was to end, as housing and land use regulations were strengthened, and especially with the urban growth boundaries and greenbelts of urban containment policy. The planning literature indicates, for example, that urban growth boundaries not only drive up land values throughout the contained urban area, but also that they are intended to (Figure 1). Advocates discount this effect, assuming that densities would increase, lowering per square foot land costs and preserving housing affordability.

In reality, ruinous housing affordability losses followed. Median multiples jumped from 3.0 or less to pre-pandemic levels of 7 to 9 (2019) in San Francisco, San Jose, Honolulu, Los Angeles and San Diego and to 5 or more in the Seattle, Denver and Portland markets. Median multiples exceeded eleven in Vancouver and Sydney, over eight in Auckland, Toronto, and Melbourne, and over five in Adelaide, Perth, and Brisbane. Further, house price increases were concentrated in land cost, with little real construction cost increase.

These developments were consistent with analysis by OECD, which still supported urban containment, but warned that sufficient developable land be available within urban growth boundaries to retain housing affordability (in Rethinking Urban Sprawl: Moving Toward Sustainable Cities). Brookings Institution economist Anthony Downs warned that preserving a competitive land market was a necessary to retain housing affordability.

It is hard to imagine a more destructive agglomeration effect than reducing the standard of living. Yet this is what the loss of housing affordability does. The middle-income material standard of living is lowered by an excessively prohibitive cost of living. Lower-income households are even more disadvantaged, many losing their independence, cosigned to subsidized housing and other welfare programs.

The Standard of Living Important Enough to Save

Modern affluence may be the supreme accomplishment of humanity over the last two centuries, with its elevation of a large, property-owning middle class. This was most evident in the United States, Canada, and Australia, as well as in the United Kingdom, Japan, Europe, South Korea and has spread to China and beyond. This is an advance that should not be sacrificed.

Appropriately, Glock concludes, “environmentalists should embrace the same future that most Americans have already chosen.”

This piece first appeared on New Geography.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy firm located in the St. Louis metropolitan area. He is a founding senior fellow at the Urban Reform Institute, Houston, a Senior Fellow with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy in Winnipeg and a member of the Advisory Board of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University in Orange, California. He has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers in Paris. His principal interests are economics, poverty alleviation, demographics, urban policy and transport. He is co-author of the annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey and author of Demographia World Urban Areas.

Mayor Tom Bradley appointed him to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (1977-1985) and Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich appointed him to the Amtrak Reform Council, to complete the unexpired term of New Jersey Governor Christine Todd Whitman (1999-2002). He is author of War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life and Toward More Prosperous Cities: A Framing Essay on Urban Areas, Transport, Planning and the Dimensions of Sustainability.

Photo: La Citta Vita, via Flickr under CC 2.0 License.