Stop Bashing Suburbs As Worst Places For Older People To Live

Suburbs and automobiles are necessary bedfellows in the United States, but this is why many experts believe that these low density, physically spread-out communities are the worst places for older persons to live. This assessment should be taken seriously. We know that transportation requests are the leading concern of older callers to the Eldercare Locator service funded by the U.S. Administration on Aging.

However, as I show below, the suburbs are becoming more amenable to a rapidly aging population. Much of this has to do with technological changes — ride-hailing services, e-commerce, social media, and information/communication advances — that make long-term suburban living more viable than imagined just a short time ago.

The Case Against Aging in Suburbia

As older persons age into their late 70s and 80s, the onset of mobility limitations—physical, cognitive, psychosocial, and financial—results in their having sharply lower vehicle trip travel and vehicle licensing rates. Lower income persons, racial and ethnic minorities, and women are especially vulnerable. Even when older people continue to drive, they restrict their out-of-home activities by not traveling at night, or in challenging traffic conditions and in poor weather. The consequences are devastating because older persons (age 65 and over) make 90% of their trips in their private vehicles (cars, SUVs, and trucks) and reaching destinations by public transit and walking is usually impossible or extraordinarily time-consuming. The result is that about a third of older people report having unmet travel needs with many stranded in their homes. Unable to satisfy their necessary (e.g., food, health care, and social relationships) or discretionary needs (leisure and recreation), they have had difficulty aging in place successfully, that is, attaining healthy, independent, active, and enjoyable lives in their current residences.

There is good reason to worry. About two-thirds of the older population living in U.S. metropolitan areas occupy the suburbs, but this share is closer to 87% in our largest metropolitan areas (over 1,000,000 in size). Moreover, suburban counties are graying faster than the core cities of metropolitan America. In particular, in the largest metropolitan areas between 2010 and 2016, 90% of the growth of older persons occurred in their suburbs. These demographics result in growing numbers and shares of low-density suburban communities predominantly occupied by older persons, residential concentrations referred to as NORCs or naturally occurring retirement communities. The prevalence of these settlement patterns will only increase as the older population in the United States grows in number by 44% between 2020 and 2040, from 56.1 to 80.8 million. And, by 2040, over half of the age 65 and above population will be age 75 and above, at higher risk of having mobility limitations.

New realities

Increasingly though, the negativism of our critics is no longer warranted as the suburban old confront fewer transportation challenges. The vehicle travel and licensing rates of older women are increasing because unlike earlier generations of females, they learned to drive in their younger years. Larger numbers of suburbs are becoming pedestrian-friendly because of redevelopment efforts or built-from-scratch communities. Older persons also benefit from new automobile technologies, such as emergency braking, and lane departure, collision, and blind spot warnings that make their vehicles easier and safer to use. In the future, semi-autonomous and driverless vehicles will make it possible for even mobility limited older persons to reach their destinations.

Older persons also benefit from ride-sharing travel services, Uber and Lyft. Unlike traditional demand-responsive transportation options, they do not require older persons to schedule their trips in advance and restrict where and when they travel. To counter affordability constraints, some local governments subsidize the fares of these services. Additionally, Uber and Lyft are collaborating with home care companies and health care facilities to make it easier for these care providers to transport their impaired older clients.

New delivery strategies to the rescue

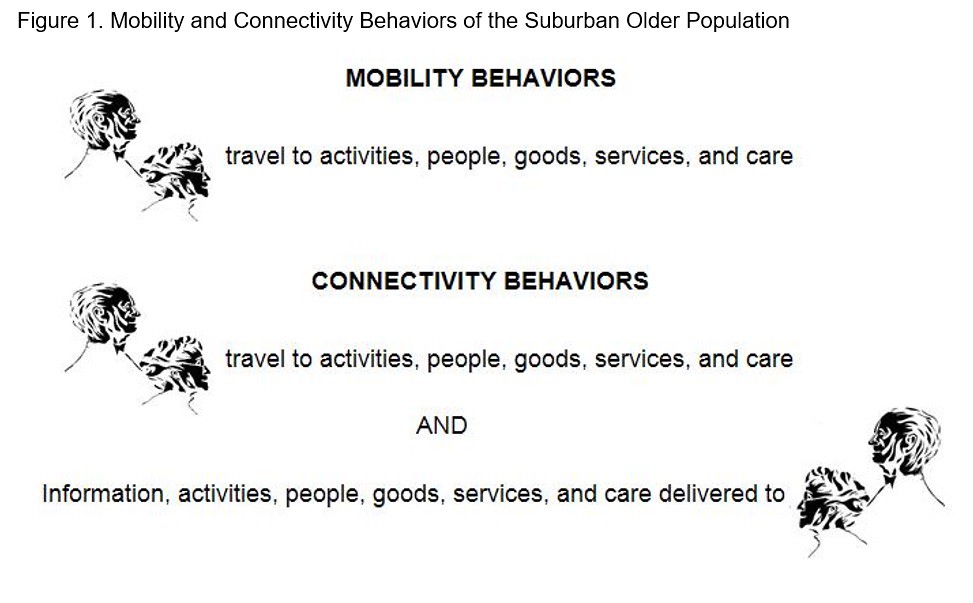

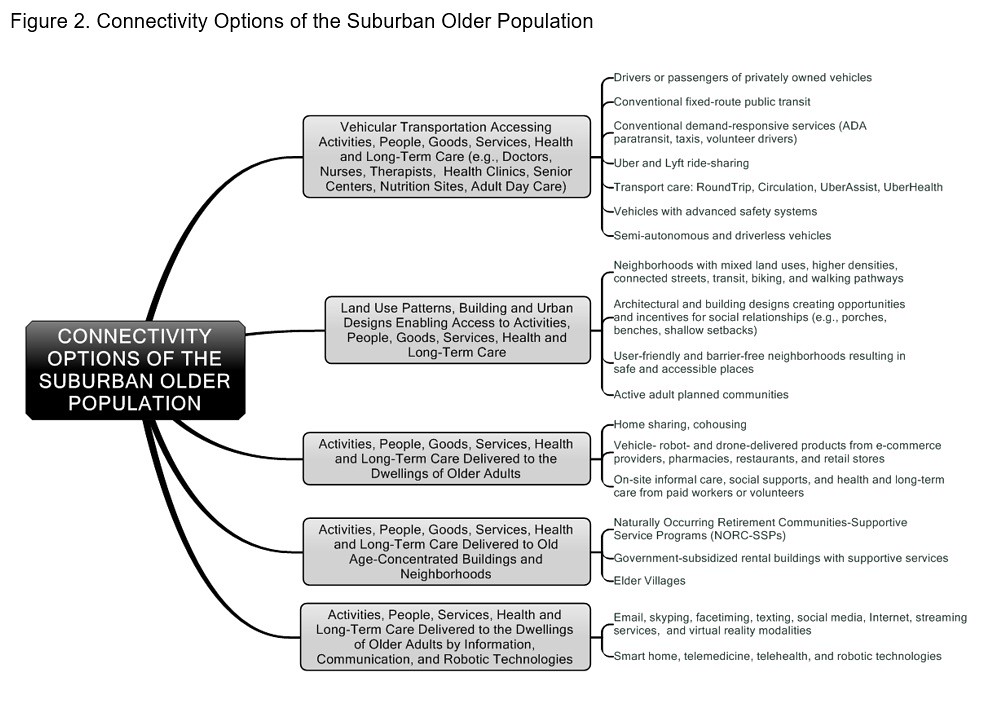

Suburban bashing is especially unwarranted because critics rely on an outmoded analytical framework that ignores the new technological realities. Older people are benefiting from a wide array of options enabling them to have information, activities, goods, services, and care delivered into their own homes and to have situ social relationships that minimize feelings of loneliness and social isolation (Figures 1 and 2). These innovations greatly increase the connectivity options and behaviors of older people. These not only encompass the traditional travel modes of transportation (cars, transit, walking) to reach destinations, but also the ways older people — without leaving their homes — can benefit from the opportunities and resources found in their suburban environments.

Three delivery strategies are worth distinguishing.

First, is the tremendous growth of e-commerce businesses. The Amazons of the world enable mobility-limited older persons to have all types of goods delivered to their homes—from toilet paper to raised toilet seats and drug prescriptions—via trucks, drones, and eventually robots. Food delivery options are especially pervasive with older persons able to access a growing number of privately-operated commercial services (e.g., GrubHub).

Older persons also benefit from an extensive infrastructure of health and home care services to help recuperate from hospital stays and over the longer term to help perform self-care and homemaking activities. Even house calls by doctors are on the rise again. By sharing their households with family members, friends, or boarders, older persons do not have to rely on their own mobility behaviors to satisfy their shopping needs. The housemates literally become their legs to reach destinations. Charitable organizations and private home sharing companies now pair older persons with appropriate boarders. Municipalities also encourage these household arrangements by changing their zoning ordinances to allow accessory units, mother-in-law suites, or on-site cottages in their single-family zoned neighborhoods.

Second, NORCS make the home delivery of these goods and services more economically and organizationally feasible. These residential concentrations or clusters of older persons provide lucrative markets to vendors and providers who deliver products and services. For example, a home care provider can make a single trip to a building or neighborhood enclave of twenty older clients and more efficiently and less expensively address their needs rather than spending the fuel and time to target the same number of recipients who are geographically dispersed across multiple and spread-out suburban locales.

Third, our digital economy now enables older Americans to access new sources of information, self-help, distant learning, online services (e.g., banking), entertainment and leisure activities in the comfort of their homes. Online streaming providers such as Amazon and Netflix offer almost limitless home entertainment experiences. Voice-controlled speakers, such as Amazon’s Echo and Google’s Assistant, can play music, read news, set alarms, provide task reminders, and answer questions. Virtual reality applications enable real-world recreational and leisure experiences. Older adults now have intimacy-at-a distance social relationships in real-time because emailing, instant messaging, skyping, and facetiming enable both textual and face-to-face interactions with their loved ones. Robotic “pets,” such as the ParoTherapeutic (baby seal) are now available as social companions or as “social interaction partners.” Home-based sensor-operated (smart home) solutions also reduce out-of-home travel and detect and respond to the potentially dangerous or limiting mobility behaviors of older persons. Home telehealth or telemedicine devices now enable older people to receive medical diagnoses and care once only available in clinical or hospital settings.

These evolving connection strategies will result in a more self-reliant suburban older population. However, these solutions are far from perfect. They will not benefit the suburban old who favor traditional travel solutions and who judge these new delivery options as inefficacious and difficult to use. Notably, affordability and technical complexities persist as adoption barriers. Older people also rightfully worry about the many unintended consequences (collateral damages) of their adoption behaviors. Foremost are privacy concerns, fear of the unknown, and distress of lost “outside” human contacts. Yet, altogether, the increasing availability of these connectivity options and the steadily higher adoption rates of older persons significantly weaken the concerns of our suburban critics.

The scope and potential of these connectivity options demand that we rethink what the World Health Organization refers to as age-friendly communities. Critics propose that our suburban elders should pack up en masse and move to higher density city locations. Instead, we should refocus our planning efforts to make our newest travel and home-delivery solutions more available and acceptable to even the most resistant and mobility limited older persons, so they too may age in place successfully—and in the communities they prefer to remain in.

Stephen M. Golant, Ph.D., is a leading national speaker, author, and researcher on the housing, mobility, transportation, and long-term care needs of older adult populations. He is a Fellow of the Gerontological Society of America, a Fulbright Senior Scholar, and Professor Emeritus at the University of Florida. A prolific author, Golant has written or edited over 140 papers and books; his latest, Aging in The Right Place, is published by Health Professions Press. Contact him at golant@ufl.edu.

Photo: Bill Dickinson, via Flickr, using CC License.