A Look At Demographia’s Latest Housing Affordability Survey

*In this interview, Wendell Cox talks about Demographia’s latest housing affordability survey. Wendell Cox is an American urban policy analyst and academic. He is the principal of Demographia (Wendell Cox Consultancy). The survey is co-authored with Hugh Pavletich of Performance Urban Planning.

Hites Ahir: You recently released the 16th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey: 2020. Tell us about the housing affordability measure used in the survey.

Wendell Cox: Demographia uses the “median multiple,” which is the median house price divided by the median household income. This measure meets two important requirements for assessing middle-income housing affordability; it evaluates the relationship between housing costs and household incomes, and it measures the middle of the market.

Hites Ahir: How does your measure compare to other existing measures?

Wendell Cox: Demographia presents current housing affordability between markets as well as in an historical context. This may be the most important difference with other measures, which often consider only recent experience, limited to only a few years or a decade or two.

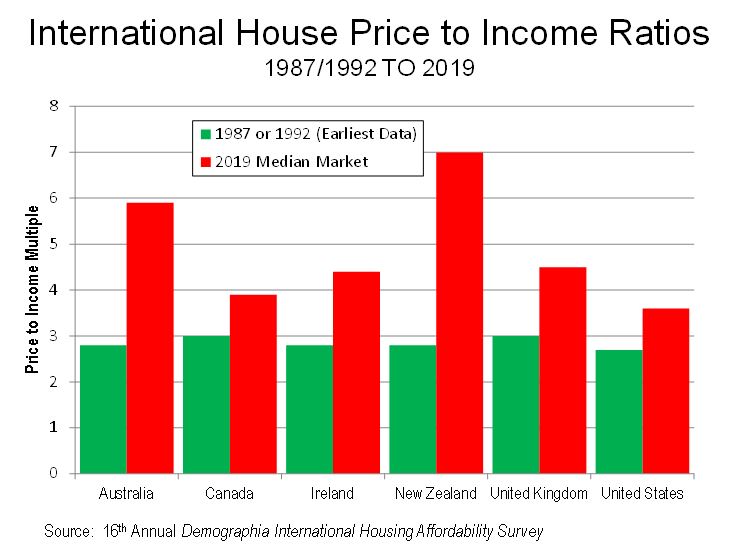

In many metropolitan markets, housing affordability has deteriorated significantly in the last three decades, from a time that in many nations the median multiple was 3.0 or below.

Figure 1.

Hites Ahir: Which countries and cities does it cover?

Wendell Cox:The Survey includes Australia, Canada, China (Hong Kong), Ireland, New Zealand, Singapore, the United Kingdom and the United States. The principal focus is on the more than 90 major housing markets areas (metropolitan areas) with more than 1,000,000 residents. More than 200 additional smaller markets are also included.

Hites Ahir: What is the overall message from the latest survey?

Wendell Cox: The message of this edition as well as the entire series is that governments should closely monitor housing affordability, to position themselves to restore it where it has been lost and maintain it where it remains.

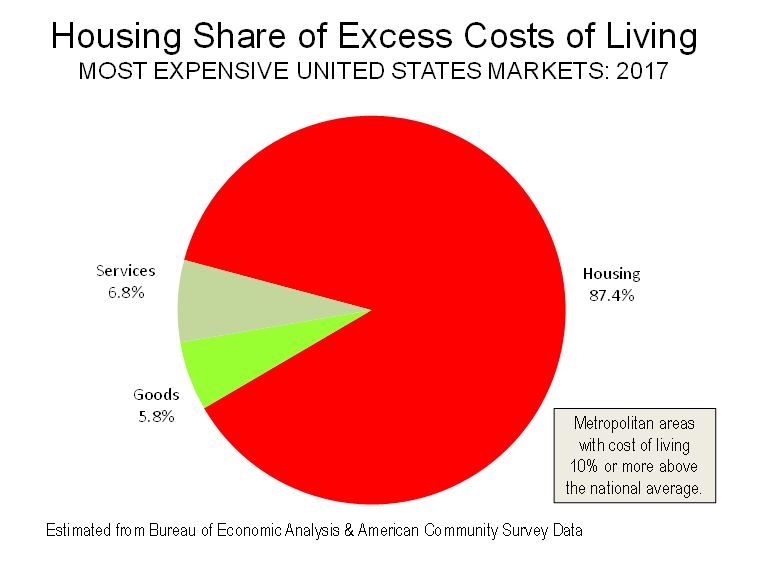

The costs of housing largely define differences in the cost of living and thus, the standard of living. In the United States, we estimate that 87 percent of the excess cost of living in higher cost metropolitan areas is comprised of housing costs.

This is an international problem, as is indicted in recent Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) research, Under Pressure: The Squeezed Middle-Class, suggests an existential threat to the middle-class in OECD countries. According to the OECD, the costs of living have risen much more rapidly than household incomes over the past three decades. Housing, according to the OECD, has been “the largest spending category” and “has been the main driver of rising middle-class expenditure in recent decades.” According to the OECD, owned housing costs have contributed more to the problem than those of rentals, though rental cost increases have been significant.

Figure 2.

Considerable economic research has associated diminished housing affordability with more restrictive land use regulation. In the Demographia Survey, virtually all of the major housing markets that are “severely unaffordable” have urban containment (such as urban growth boundaries and other policies that severely limit or prohibit new development on the urban fringe).

Research in Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States has found comparable land values spiking 10 times and more across urban growth boundaries. Within the San Francisco metropolitan area, economists Edward Glaeser of Harvard and Joseph Gyourko of the University of Pennsylvania found land values for median value houses were “roughly 10 times” the “minimum profitable production cost.” This is in a market stretching across five counties, with ample suitable land, nearly all of it off-limits to development.

There is need for reform, and we cite Paul Cheshire, Max Nathan and Henry Overman of the London School of Economics who suggest that urban planning should focus on “people rather than places.” Part of the solution, according to former World Bank principal planner Alain Bertaud, is to apply “basic economic principles to the practice of urban planning.”

Hites Ahir: How does the findings of this editions compare to the past editions?

Wendell Cox: We have reported on the commitments made by New Zealand’s Labour government to make major land use policy revisions to restore housing affordability and establish effective infrastructure finance mechanisms.

We have also focused on subsidized low-income housing and the extent to which its cost and availability is driven by market housing costs. Because housing subsidies are typically based on ability to pay, deteriorating housing affordability compromises the ability of government to provide for low income housing.

Hites Ahir: In the current issue of the survey, you talk about Singapore. Could you talk to us about “Singapore’s unequalled housing challenge”?

Wendell Cox: Singapore is a city-state confined to an island that has virtually no hinterland in which inexpensive housing development can occur. Yet this topographically contained market has housing affordability considerably better than many markets that have administratively imposed urban containment.

Singapore designed a market that kept house price increases under control, despite the shortage of land. It started with a commitment, more than a half-century ago, to “(…) encourage a property-owning democracy in Singapore and to enable Singapore citizens in the lower middle-income group to own their own homes.” The mandate was assigned to the Housing Development Board (HDB) which has delivered on the objective.

Singapore’s model for the world is not so much the characteristics of its market, as it is having adopted a fundamental objective of housing affordability and focusing on its achievement.

Hites Ahir: How is the ongoing crisis related to Covid-19 likely to affect next year’s survey?

Wendell Cox: Obviously, the economic decline from the lockdowns will make things worse, and probably more for the middle-income households we focus on. Lower-income households are likely to be impacted even more. Housing affordability seems more likely to worsen than to stay the same or improve.

This piece first appeared at The Unassuming Economist and is reprinted here with permission.

Prakash Loungani is an Assistant Director and Senior Personnel & Budget Manager in the IMF’s Independent Evaluation Office (IEO). He is also an adjunct professor at Vanderbilt University’s Owen School of Management. He has 25 years of job experience at the IMF, the Federal Reserve System and the University of Florida. He blogs as The Unassuming Economist.

Photo credit: Erwin Soo via Flickr under CC 2.0 License.