Houston, City of Opportunity

This essay is part of a new report from the Center for Opportunity Urbanism titled “The Texas Way of Urbanism”. Download the entire report here.

Creative friction – unchaperoned and unprescribed – is Houston’s secret sauce.

At a time when Americans’ confidence in all major U.S. institutions – minus the military and small business – has sunk below the historic average, and only about 20 percent of Americans say they spend time with their neighbors, one would expect pessimism to be universal. But come to the concrete sprawl just north of the Gulf and you’ll find a different vibe, one that other cities would do well to emulate.

Of course things aren’t perfect in Houston, and the region is taking it a bit on the chin due to the drop in oil prices. But look over the mid- and long-term and the place has consistently lured people from around the country and the world.

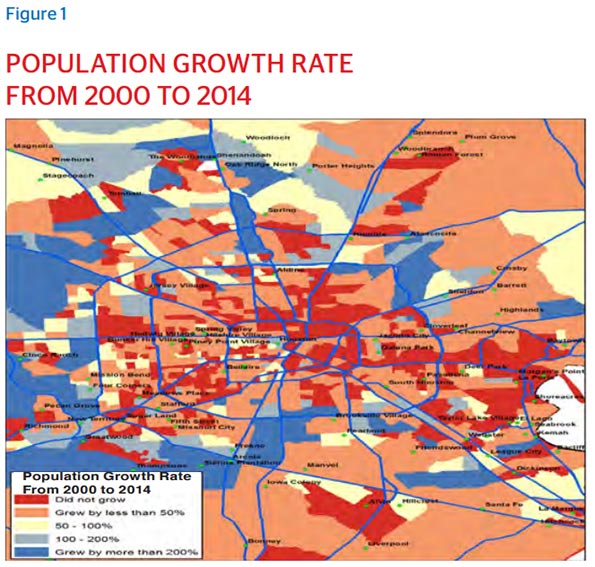

People continue to move to the flat and humid city in higher numbers than any other metropolis. According to the United States Census Bureau, from 2014-2015 metro Houston attracted 159,083 total and 62,000 net domestic migrants, topping the Census list on new metro area residents. Critically, the newcomers represent those population groups most telling of a metro’s future: millennials, immigrants, and families.

“The American Dream is still alive here,” say those migrants, one after another. 81 percent of Houston residents rate the city as a good or excellent place to live, according to the 2016 Kinder Houston Area Survey. That’s up from 70 percent a decade ago. And despite the recent economic slowdown, 62 percent of Houston-area residents rated the local economy as “excellent” or “good.”

Even the most conventional of popular figures have begun to figure this out. “Houston will surprise you,” wrote Katie Couric when she stopped here on a nationwide tour of up-and-coming cities. It was a more iconic statement than perhaps she realized. Outsiders often misperceive Houston as politically conservative and totally dependent upon the energy business, but the city consistently busts internal expectations, too. In Houston, you don’t have to drive far to run into unexpected languages, unexpected restaurants, a huge informal economy and just a pervasive – and bracing – sense of random.

“It’s a cat city,” says Bill Arning, director of Houston’s celebrated Contemporary Arts Museum. He moved here in 2009 from Boston. “If you arrive without a tour guide, without a friend who knows the city, it’s hard to figure out where things are. There are no landmarks. Whereas Austin is a dog city – you know where the beautiful people are – Houston is a cat city. Its charms are there, but you’ve got to come to it. You’ve got to take a little time.”

What sets Houston apart? What about the city makes so many residents confident they will find their version of the American dream here? If it is indeed a city of opportunity, what lessons might other cities absorb and weave into their own policies and cultural fabric? Through many interviews, data sleuthing and the everyday experience of living here, I found five traits that define Houston: affordable proximity, multipolarity, social deregulation, an active future orientation, and humility. What follows is a tour of the city that knows no limits.

Affordable Proximity

“There’s always been a haphazard nature to the city, from the beginning,” says Sanford Criner, a native Houstonian as well as vice chairman at CBRE, the world’s largest real estate firm. “Where Chicago – which was founded the same year [1836] – had an economic reason for being the day it was founded, Houston was a real estate play. These guys came down from the northeast – New York, Pennsylvania – and they bought some land and sent out flyers.

“I’ve seen some [of the flyers], and they’re hysterical,” Criner continues. “‘Salubrious environment!’ said one. ‘Well-watered!’ said another. They’d have this picture that looks like a little Swiss valley, with chalets up the hill, and there wasn’t a house here! It was a scam. But that’s how we now date the founding of our city.”

Where others saw only wilderness along the banks of Buffalo Bayou, Augustus Chapman Allen and John Kirby Allen saw promise, and convinced people to take a gamble and move. This rambunctious “come one, come all” attitude continues to define the city’s development, 180 years later.

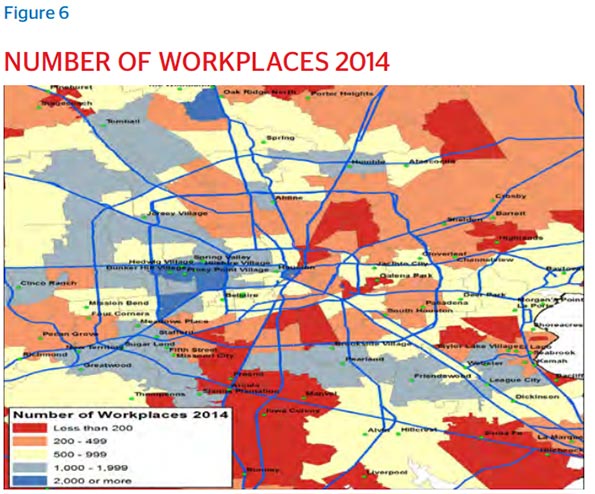

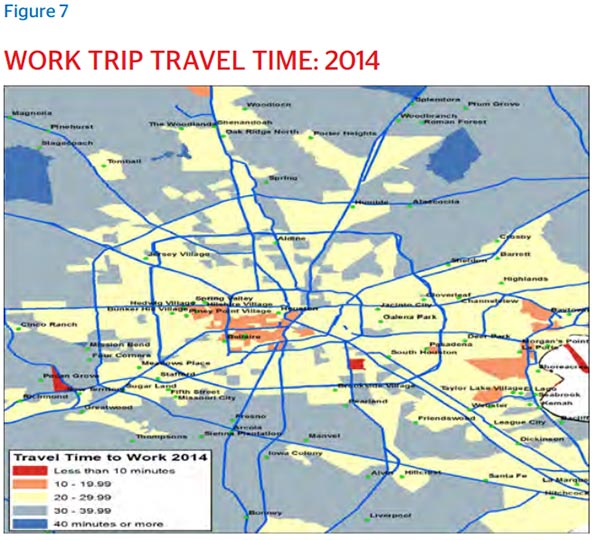

The city of Houston is famous for its no zoning policies, the fruits of which are visible in the hodge-podge of commercial and residential hubs evident on a first drive in from one of the two airports. The apparent haphazardness may dizzy outsiders, but for Houston residents it’s a gift that my colleague Tory Gattis calls “affordable proximity”: the ability to live near one’s place of employment while keeping the cost of living affordable. It’s a challenge that has become onerous in many cities, but one that Houston manages to tackle with surprising efficiency.

“It’s definitely true that it’s easier to build things here than elsewhere,” says Criner. “We’ve been able to build things relatively inexpensively and rapidly that have generally benefited everybody.”

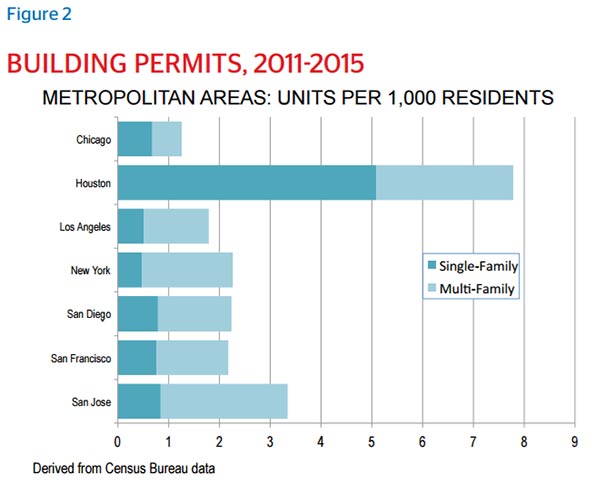

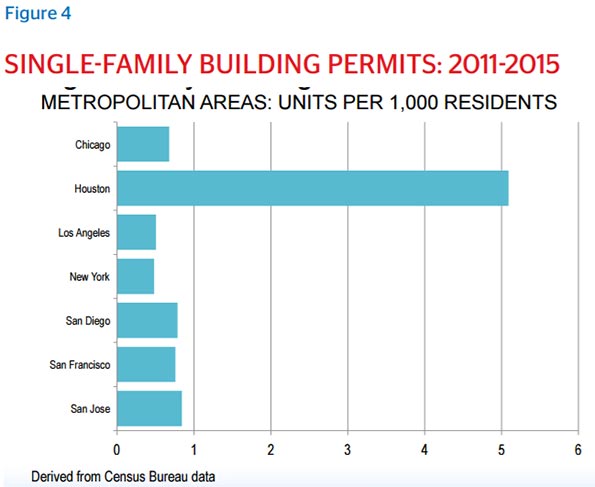

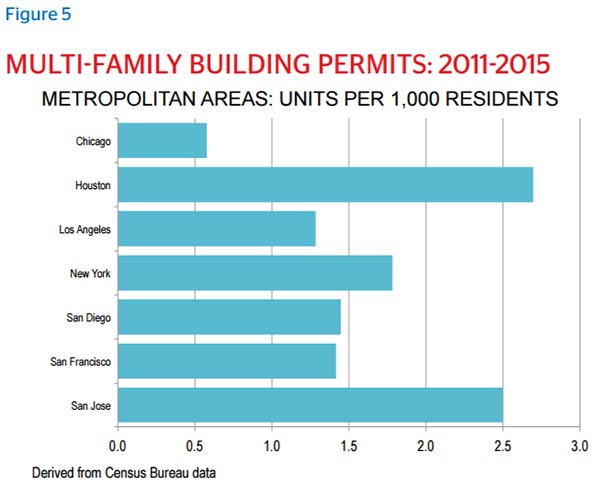

Since 2010, Houston has expanded its housing stock to issue construction permits for 189,634 new units, paralleling the population growth. This is in sharp contrast to competitor cities such as New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and the Bay Area, where construction tends to lag behind population.

Houston is uniquely able to create housing to meet demand. The populations in both New York City and Houston have grown significantly in the past six years, but New York, like many big cities, has not come close to meeting demand. A lot of this has to do with sheer land availability and willingness to expand outward, but Houston’s light regulatory touch has crucially allowed developers to be in sync with consumer need and preference, without the red tape that slows other cities’ building and adaptability. A key result has been a greater level of affordability, and of choice.

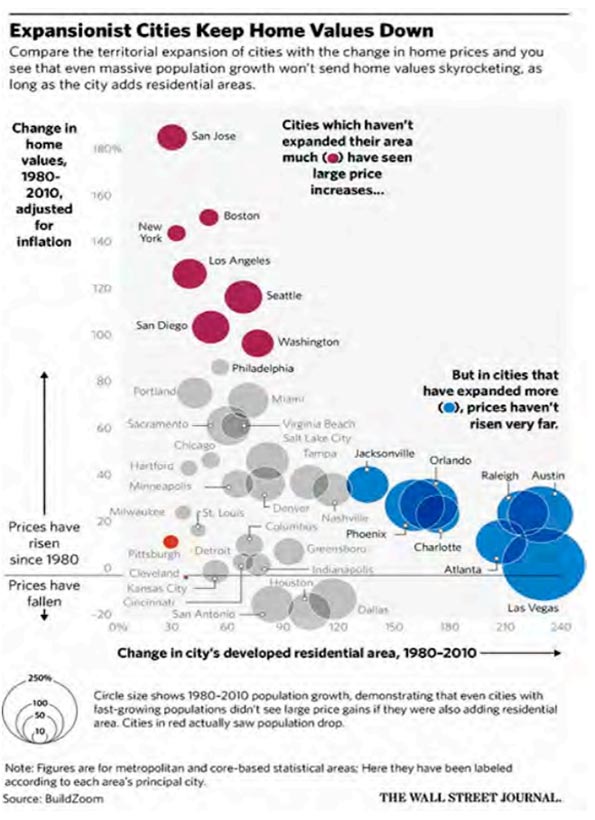

In April of 2016, The Wall Street Journal highlighted groundbreaking research by Issi Romem, chief economist at real-estate site BuildZoom, showing that the cities that have expanded geographically have kept their house prices more affordable.

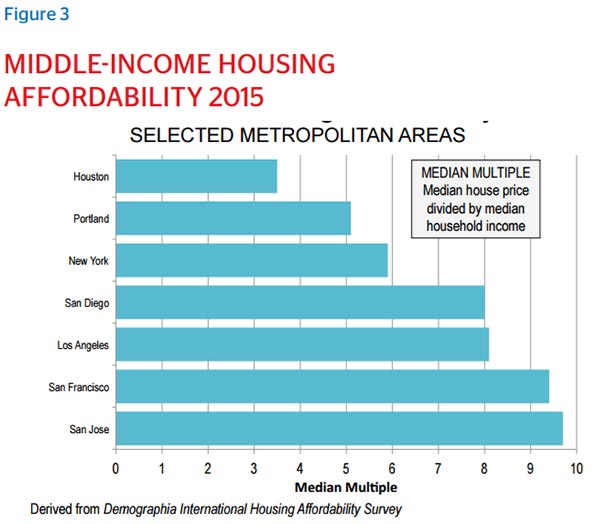

According to the National Association of Home Builders/Wells Fargo Bank Housing Affordability Index, more than 60 percent of homes in the Houston metro area are now considered affordable for median-income families, compared with only 15 percent in Los Angeles, once ground zero for the dream of homeownership. According to Zillow, renters in New York spent 41.4 percent of their income on housing in 2015, whereas the share for their Houston counterparts was just 31 percent.

The Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey provides ratings for all major metropolitan areas in the U.S., and Houston consistently ranks as more affordable than cities like Portland, New York, San Francisco and San Jose, all of which have more restrictive regulations.

Houston’s housing is also diverse. Houston has become the national leader in new multifamily units, helping to preserve and expand access to urban living. At the same time, the Houston metro has led the country in new single-family houses.

Availability of affordable land and a lighter regulatory environment allowing for outward expansion has made it possible for many to afford a residence near the city’s dispersed job centers. In addition, as City Observatory recently reported, a series of reforms adopted in 1999 shrunk the required residential lot size from 5,000 square feet to 1,400 square feet, enabling town home development in high demand areas proximate to jobs.

Proximity to work is especially appealing to millennials, who have moved to Houston in droves. The U.S. Census Bureau showed a 25 percent increase in millennial residents between 2000 and 2013, with millennials currently making up 24 percent of Houston’s total population. Many of these new adults want to reduce their commutes, or even ditch their cars for the sake of enjoying a more seamless transition between professional and personal life. Houston offers this possibility across urban and suburban areas, the multipolarity of business centers providing flexibility to carve a nice triad of work, residence, and play.

Despite the impression of endless freeways, Houston’s commute times are better than those in metros of comparable populations. One-way commutes were 28.4 minutes in 2014, according to the American Community Survey, making Houston the fourth best out of nine comparable cities.

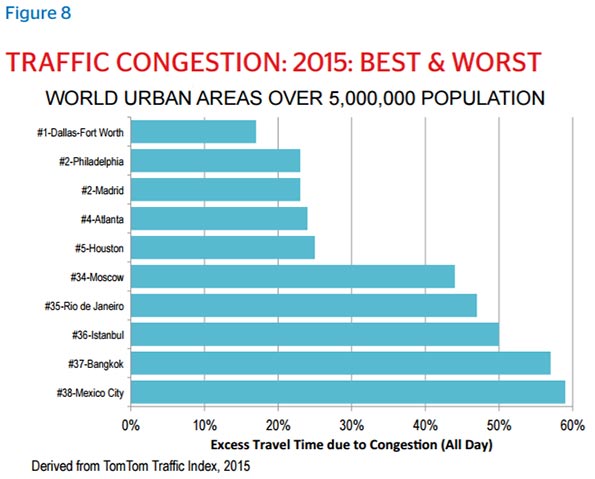

Houston also does very well on an international scale with respect to traffic congestion, according to TomTom in 2015. The region ranked fifth out of the 38 urban areas that have populations over 5 million.

None of this suggests Houston lacks room for improvement in mobility, but it’s credit to the city’s decision to dramatically increase roadway capacity and arterial streets that it has managed to improve its ranking in traffic congestion while experiencing a huge increase in population. According to the Texas A&M Transportation Institute, in 1984 and 1985 Houston was ranked with the worst congestion in the country, even worse than Los Angeles. Now Houston is ranked 10th, even as it’s nearly doubled its population, from 3.5 million in the mid-1980s to 6.5 million today. Only Atlanta and Dallas can boast similar mobility improvements.

Multipolarity and Economic Diversity

Most Americans think of Houston as an oil and gas town. And while energy still undergirds much of the city’s economy, Houston boasts many other assets as well: the world’s largest medical center, one of the world’s busiest ports, the third largest manufacturing hub in the country, a booming technology sector and a wide range of small to medium-sized businesses, including a thriving informal sector of immigrant-run businesses. This has led to demand for labor at all skill and education levels, unique among the top ten largest cities.

“Best Online Programs in 2016,” said U.S. News & World Report about the University of Houston. “Top Cities for Competitiveness to Attract Investment in Chemicals & Plastics,” said Conway about Houston in 2015. “Best Hospitals for Adult Cancer – University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center” said U.S. News & World Report in 2015. “Top Blue-Collar Hot Spots,” said Forbes in 2014. “Most Favorable Metro for STEM Workers [Nationally],” said WalletHub in 2015.

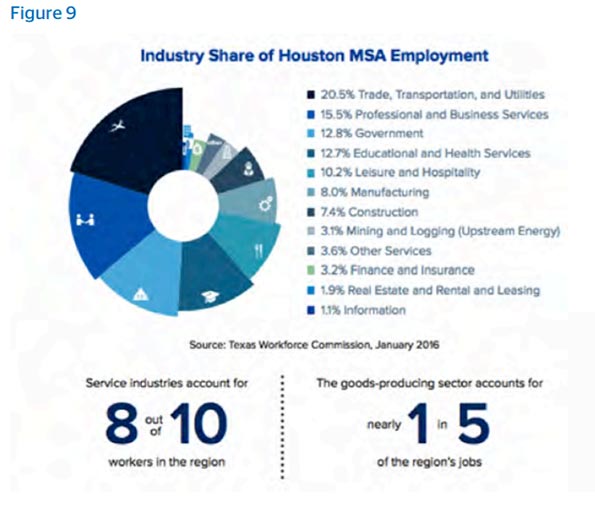

Houston is no stranger to “Best Of” lists that today’s mayors scour. But what’s notable is the cross-sector nature of the superlatives. According to a June 2016 report from the Texas Workforce Commission, 20.3 percent of Houston’s workers are in Trade, Transportation and Utilities, 15.5 percent are in Professional and Business Services, 12.8 percent in Government, 12.7 percent in Education and Health Services, 10.2 percent in Leisure and Hospitality, 8 percent in Manufacturing and 7.4 percent in Construction.

The city has learned from its mistakes. The 1980s, which saw a slump in oil prices much greater than that in 2015, bulged in profligate building and overconfidence. According to the Greater Houston Partnership, from 1982 to 1986, developers built more than 100,000 single-family homes, many of them without a signed contract from a purchaser. Even when the region lost more than 200,000 jobs, office developers continued to build, including adding more than 71.7 million square feet of office space while companies were laying off staff and declaring bankruptcy. Today, the office market is tighter, banking is better regulated and better capitalized, and few homes are built without a signed contract. Most importantly, the region is creating jobs that aren’t in energy, including in health care, business and professional services.

Social Openness: A City for Everyone

Houston is deregulated economically, but it’s of greater note that it’s deregulated socially. People come here from many walks of life and culture, and the relative youth of the city combined with its scrappy DNA means that there really isn’t a dominant Establishment, certainly not one that wants to block the efforts of ambitious newcomers.

“If you talk to [old] Houstonians about social mobility,” says Sanford Criner, “they kind of give you this quizzical look. Like, ‘what do you mean?’ Like, ‘Sure, of course.’ It seems obvious.”

This city’s always been a mixer; you just have to be willing to share what wakes you up in the morning. Marlon Hall is an African American filmmaker and native Houstonian who started Folklore Films, a documentary production company created to “tell better stories to our city about our city.” He and fellow filmmaker Danielle Fanfair have featured former Mayor Annise Parker, arts patron Judy Nyquist, internationally recognized musical artist DJ Sun and other community figures. As the Folklore Films crew has gotten better acquainted with Houston residents from across the social spectrum, Marlon locates the vocational “why” as central to the city’s currency.

“Houston isn’t driven by who you know,” he says, “but by how you want to be known. It isn’t about what pedigree you have received, but about the possibilities you want to bring to bear.”

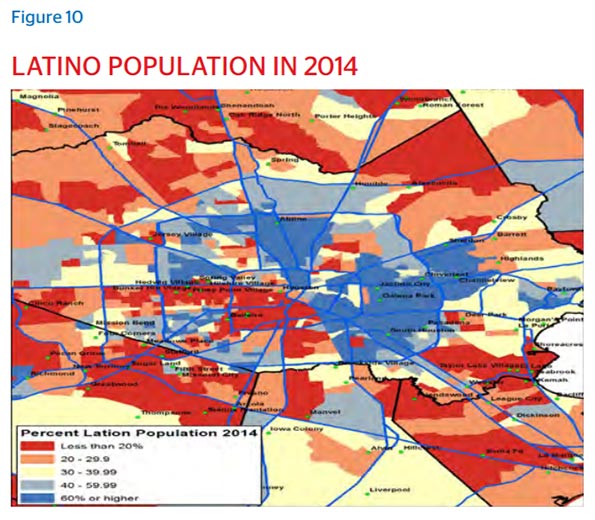

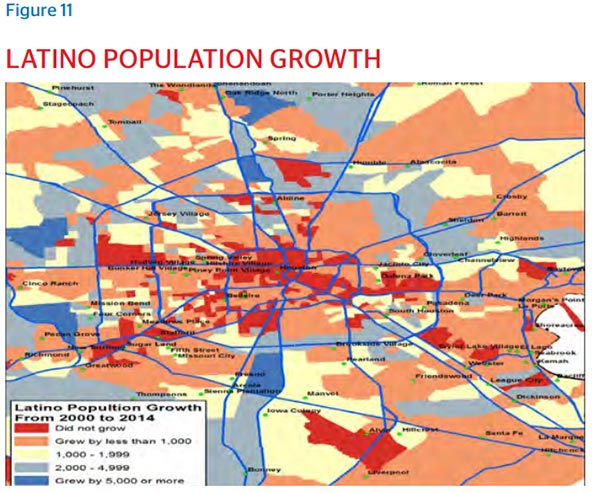

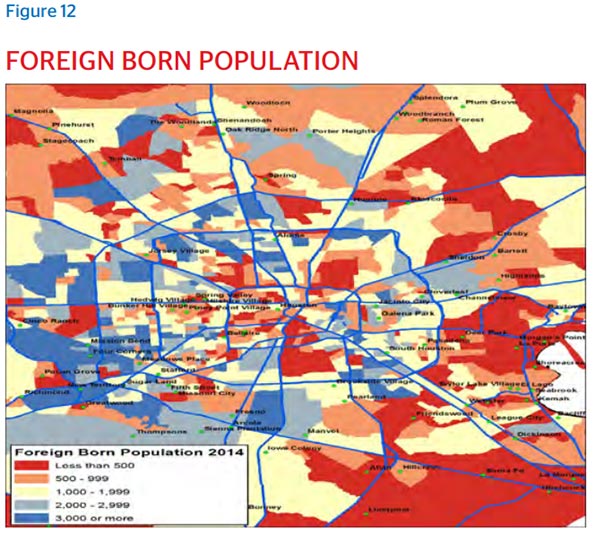

This kind of invitation has attracted the motivated from all over the world, with the city now pulsating with 145 languages. An international city since the day it was founded, now more than one in five Houstonians are foreign-born, with the 2014 American Community Survey reporting that 63.9 percent of the foreign born population were Latin Americans, 25.2 percent were Asian, 5.1 percent were African and 4.6 percent were European. As of the 2010 Census, Greater Houston does not have a majority racial or ethnic group.

People come to Houston seeking opportunity, and because they sense in the visible randomness the potential for surprise ingredients to leaven the traditions they’re bringing with them. This is as true for immigrants as well as domestic migrants, with the city’s celebrated restaurant scene born out of the unexpected merging of flavors from cultures that don’t typically mix. Underbelly’s Chris Shepherd, Bistro Menil’s Greg Martin and Lucille’s Chris Williams all cite Houston’s diversity as a major factor behind the city’s flavorful palate, in both story and succulence.

“This is edible history,” says Chris Williams, the founding chef at Lucille’s, a restaurant that takes a modern approach to Southern classics. “The food that we do here pays homage to my great-grandmother, who was a chef and a pioneer and an American icon.”

It’s not soul food, but Southern. With a rustic European style, and a multi-generational American story at the heart.

“Like all chefs in [my great-grandmother’s] time, your style of food was defined by what was available to you. What you could afford to work with. The flavors that I grew up with…married with the techniques and the flair that I picked up working in Europe for four years. Everywhere from London to Lithuania. …I’m influenced by the simple rustic dishes – the ones about the culture, not the flashy ones. The perfect piece of fish fresh caught, served with good potatoes, great olive oil, fresh garlic, and a little bit of parsley.”

Bistro Menil is another spot that takes a slice from Europe and re-interprets the classic dishes for Houstonians. Its patrons come from Rice University, the Medical Center, the Museum District and beyond, the attraction of the world-renowned Menil Collection standing just across the street. Inspired by the concept of cask wine, which head chef Greg Martin discovered on a trip to Rome, Bistro Menil relies heavily on relationships with cosmopolitan – yet locally centered – Houstonians.

“I don’t want to compete with that dish that you had in Rome,” Martin says, aware of ingredient limits this side of the Atlantic. “I want to reinterpret it with more of a New American approach, with some fresh eyes on our market, using our ingredients. Our ingredients and produce come from everywhere…I work really closely with a local importer. We’ve been working together for 30 years. He brings in our duck legs from Canada, our jamón Serrano from Spain. He brings all of our cheese in from France, Italy and Spain.”

It’s not just the food that shows Houstonians willing to work together across silos and lift up the local talent. “We have a very supportive gallery scene,” says Bill Arning, of the Contemporary Arts Museum. “Even the galleries that show a lot of major international and national artists, like the Texas Gallery and McClain Gallery, will not only show local artists, they’ll place them in the top collections in town. That’s unusual.”

The social egalitarianism combined with a pervasive “show me what you got” curiosity creates something very unique. Hipster cocktail bars seem no more privileged than authentic Vietnamese restaurants than classic barbecue and the iconic Rodeo. The lack of zoning makes thoroughfares like Westheimer Road, which stretches for miles from the city center to the distant suburbs, an avenue of cultural mismatches: The New York Times’-celebrated Underbelly is sandwiched between three tattoo parlors, a Catholic guild clothing store and the latest in coffee-roasted curation. There are so many opportunities to mix with those different from you that only the snobby find themselves bored and excluded. Creative friction – unchaperoned and unprescribed – is Houston’s secret sauce.

“This is a city that does not believe in censorship,” says Arning.

Agile, Active, and Future-Orientated

Houston is not Silicon Valley, but its entrepreneurial DNA is unmistakable, dispersed across many fields. The city emanates a conviction that people should have the freedom to determine their destiny, sometimes to the point of overlooking those that don’t have such clear vision, nor the resources and social networks to make it happen. The city is growth- and future-oriented, embracing change and risk. True to its namesake in Sam Houston – himself a failure before reinventing himself – Houston grants permission to fall hard.

“Houston is the only town where a person with no prior experience in a particular vocation can get joint venture capital for something they’ve never done before,” says local arts patron Judy Nyquist in one of Marlon’s Folklore Films. “Simply by virtue of their commitment to their idea, and how it can make the city better.”

This is true across sectors – for-profit, social service, and philanthropic.

Ella Russell of E-dub-a-licious Treats was an African American single mom working for AT&T when a breakup with her partner caused significant financial hardship. Her two boys, then age 3 and 9, came home from school asking to bring in treats for a holiday party. Russell felt helpless, all disposable income had run dry. But she did find sugar, flour and eggs in her pantry.

“I scraped up change to buy a bag of chocolate chips,” Russell recalls, “so I could make chocolate chip cookies. The kids took them in, and then I brought the leftovers in to work. My coworkers loved them, saying every future potluck would have to have my cookies.”

Three years later, her friends urged Russell to turn the sweetness into a business.

“I had no business experience other than what I knew working in corporate America,” Russell says. “I really winged it; I had no basis but the support of my friends.” In a couple years, she went from serving family and friends to delivering in seven different states.

In the burgeoning scholarship entrepreneurship of the last decade, the work of Saras D. Sarasvathy of the Darden Business School at the University of Virginia stands out. She’s coined a term called “effectual reasoning” to describe the mindsets of master entrepreneurs, one that pairs well with Houston’s soil:

Brilliant improvisers, the entrepreneurs don’t start out with concrete goals. Instead, they constantly assess how to use their personal strengths and whatever resources they have at hand to develop goals on the fly, while creatively reacting to contingencies. By contrast, [highly successful] corporate executives use causal reasoning. They set a goal and diligently seek the best ways to achieve it.

Sarasvathy likes to compare expert entrepreneurs to Iron Chefs: “[They are] at their best when presented with an assortment of motley ingredients and challenged to whip up whatever dish expediency and imagination suggest,” she writes. “Corporate leaders, by contrast, decide they are going to make Swedish meatballs. They then proceed to shop, measure, mix, and cook Swedish meatballs in the most efficient, cost-effective manner possible.”

If we could take her comparative study and extrapolate from it particular civic traits, you might see Chicago as the sort of personality for corporate leaders, Houston for the entrepreneurial. The city is rife with improvisers, fueled by a deep prioritization of human relationships, an affection for eccentrics and a perennial optimism that loves to build before over-planning. The fact that there are lots of open spaces to create, and fill, encourages new entrants into any kind of market, be it technological, artistic, or consumption-oriented.

This goes well beyond profit-seeking ventures. The Chronicle of Philanthropy identifies Houston as one of the country’s most generous cities, ranking at #11 for giving as a percentage of adjusted gross income – three stops behind Dallas.

“As [Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston] have each become centers of gushing economic production, and matured as communities, an energetic competition has grown up in their creation of impressive new parks, museums, hospitals, universities, and arts centers,” wrote Ari Schulman in the Fall 2015 issue of Philanthropy Magazine. “Burgeoning circles of local patriots wielding newly minted fortunes have dramatically changed the quality of life in both cities over the past decade or so.”

This enhanced quality of life has involved a deeper renaissance in the arts, a proliferation in family-friendly green spaces, advancements in medical facilities and, increasingly, innovative educational ventures. Houston’s acclaimed Museum of Fine Arts is currently undergoing a $450 million redesign, two-thirds of that already raised with the help of giant gifts from pipeline entrepreneur Richard Kinder and money-manager Fayez Sarofim. Kinder and his wife Nancy have also given $30 million to a public-private partnership aimed at reviving a snaking bayou from a stagnant waterway to an attractive waterfront graced by 20 miles of hike-and-bike trails, canoe launches, playgrounds, art installations, and outdoor performance venues.

“This kind of public-private partnership happens all the time,” says Criner. “In lots of other cities, philanthropic organizations tend to be run by the same group of guys that have been running stuff for a long time, and they treat them like their own turf. You don’t see that here at all. This is way more like, “if you can help, come on! What can you do? We’ll put you to work.”

“We have a tradition of philanthropy that my colleagues in other cities [envy],” agrees Arning, of the Contemporary Arts Museum. “Privileged young people here feel they need to find their philanthropies early on. That is something uniquely Houston.”

Humility and Cultural Accessibility

Long considered the unattractive hothouse of the south, Houston has suffered from a long-running inferiority complex when comparing itself to other cities. Even since rising to the top of dozens of “Best of” lists in the last five years, the residue from generations of modesty remains.

Before Marlon Hall was running Folklore Films, he and Danielle began something called the Eat Gallery, an incubator for budding chefs around the city that sought to turn food trucks into restaurants. In ramping up for this effort, they went around and asked Houstonians questions about where they found meaning, where they felt they fit, where they felt they made a difference. They discovered that people had low city esteem.

“They’d go to a great ballet, and they’d be like, wow, this reminds me of Chicago, Hall recalls. “They’d go to a musical performance and be like, oh, this feels like New York. People were telling the worst stories to the city about the city.

“So we said, what if we told better stories to Houstonians about Houstonians, featuring people that folks know and celebrate? But what if we began their stories with their brokenness, so that people would know that there’s something inherently broken about every beautiful person? So that’s what we did, that’s why we started Folklore Films. To raise the city esteem.”

Folklore discovered that Houston is a city of new beginnings. When you move here, the past intrigues less than how you intend to exploit the future. Whether you’re an immigrant from overseas or a fellow American that’s left some entrenched failure behind, Houston pulses with a forward-looking frankness grounded in a humility shaped by whatever came before. This drive paired with an individual and corporate self-awareness defines the city’s character – culturally, spiritually and even economically.

“There’s this at-homeness that people from Houston have,” Hall says. “When I think about people who have left Houston to do other things, like Beyonce, there’s this comfort to be who one is. She walks around with hot sauce in her purse – I mean, who else can say that from where else?”

“There’s something about Houston that’s like…I’m not afraid to be who I am, even if it’s full of seeming contradictions.”

“The collective body in Houston is significantly more adventurous than most cities,” Arning of the Contemporary Arts Museum says. “Both in use and collection. In most collection cities, you hear who supported or recommended the collection before going. Houstonians, because of their wildcat nature, [will try anything] they like.”

Houston’s increasing diversity keeps the city vibrant and ever ready to accept change and innovation. There is no room for insularity because there is no homogeneity. Your ideas are constantly being chiseled and countered by the Other. No one has the luxury of feeling superior because everyone’s in a gem tumbler with folks not like them. It makes the city competitive, but not in a way that produces monopolies.

“I think that Houston has come to this place where it’s a ‘My Space,’” says Marlon. People want to take ownership of their lives and creations here. “There’s a desire to own who you are in Houston, which is different from owning a business, a house a car.”

Houston residents tend to be proud of their individual accomplishments, and feel an affection toward the place that allowed those accomplishments to happen. But there’s a recognition that success is the result of many different pieces coming together, usually organically and iteratively. The environment invites people to fulfill their individual destiny, and almost discourages any person or governing body to take credit for Houston’s successes as a whole.

“I hesitate to say things like ‘I’m proud of Houston,’” Sanford Criner says. “What gives you the right to take pride in a place? Did you build it? Did you do it?”

Challenges to Sustaining Opportunity

Houston continues to beat the odds to this day. And while its adventurous impulse is what continues to draw people to Houston and make it the emblem opportunity city for 21st century dynamics and demographics, it must still be said that what you put into the world must survive. Houston is a much better place to live than it was 30 years ago. But will it continue on this trajectory, or even sustain the fruits of its triumphs?

Houstonians recognize there needs to be a concerted effort to reform and improve Houston’s educational opportunities, its transportation and traffic infrastructure, and a more general care to respect tradition and an intensive effort toward more inclusive mobility. The city’s grown so big, so fast, it could inevitably buckle under its own weight.

“We are not on track to make headway on a lot of the issues that are facing us,” says James Llamas, of Traffic Engineers, Inc. “We’re growing way faster than we’re adding transportation capacity or options, at the same time there does seem to be recognition that we need to do something and what we’ve been doing isn’t going to continue to work.”

Despite precedent, massive infrastructure may not be the answer, especially given the shifting preferences of a younger population and the costs of maintenance. New mayor Sylvester Turner is considering expanding to two HOV lanes and providing express bus service. Others advocate for densification of the more traditional gridded neighborhoods that are far from holding their population capacity – but without adding infrastructure, and without pushing anyone out.

And then there’s the perennial education challenges.

“We are now in a different economy where education is critical,” says Stephen Klineberg, founding director of the Kinder Institute. “It never used to be critical, especially not in Texas. You made money by land – by exploiting all the natural resources you needed on the land. The great cattle, timber, oil. The source of wealth in the 21st century Houston, is knowledge. …If you don’t have education beyond high school, with the technical skills that allow you to get the jobs of the 21st century, and compete, you’re not going to make it. Texas hasn’t come fully to grips with it.”

Conclusion

In the last 20 years, Houston has cultivated a series of signaling mechanisms that continue to draw people into its orbit. It’s a welcoming city, supported by affordability and diversity. Majority opinion says “anything is possible if you’re willing to work hard,” a conviction increasingly on the decline in the rest of the country. And, crucially, it’s cultivated the conditions necessary for entrepreneurs to have a field day. “The assortment of motley ingredients” noted by innovation scholar Sarasvathy describes Houston in a nutshell, and the regulatory instinct has been to stay light, allowing imported imaginations to run experiments without interference.

The city’s not beautiful upon first blush, nor does it offer the charm of pedestrian fancy that denser cities boast. But in an era of civic unrest, with many up and down the social spectrum feeling disconnected and robbed of agency, Houstonians can still shape their destiny. The city’s the clay; residents the potters. The wide range of home sizes and work-life arrangements makes Houston like the cowboy boot its Rodeo celebrates – adaptable to the needs of each life stage as residents progress through singleness, marriage, family and retirement. Residents are not trapped by the regulatory, financial or even social limits that other cities increasingly impose. The mindset is one of abundance, not scarcity.

“This is the genius of this place,” wrote Cort McMurray in the Houston Chronicle in January of 2016, in a profile of an Iraqi refugee who had come to Houston with a B.S. in Chemistry, currently cleaning pools. “Houston will always be shambolic and stretched and not quite finished. We will never be the most beautiful city, or the most pedestrian-friendly city, or the most efficiently planned city: The heat and soul-sapping humidity, our adolescent fascination with cars and speed and shiny things, our perpetual craving for something new, all conspire against our best civic aspirations. Houston is a place to start over, and we do starting over better than any other city on the planet.”

In an age of heightened political frustration, a sclerotic economy and shifting structural tectonics, it could be that the “starting over” ethos that Houston embodies is precisely what the country itself needs, and what other cities should seek to foster in their own policies and cultural climates. Innovation, reinvention and reinterpretation, after all, lie at the heart of the American genius.

Anne Snyder is a Fellow at the Center for Opportunity Urbanism, a Houston-based think tank that explores how cities can drive opportunity and social mobility for the bulk of their citizens. She is also the Director of The Character Initiative at The Philanthropy Roundtable, a pilot program that seeks to help foundations and wealth creators around the country advance character formation through their giving. She previously worked at The New York Times in Washington, as well as World Affairs Journal and the Ethics and Public Policy Center. She holds a Master’s degree in journalism from Georgetown University and a B.A. in philosophy and international relations from Wheaton College (IL), and has published in The Atlantic Monthly, National Journal, The Washington Post, City Journal and elsewhere.

Top photo: Photo by Chris Doelle, Licensed under CC License.